Last week I wrote a brief introduction as to why I’m so interested in pottery — and all ancient artefacts made out of clay for that matter… (link at the end if you haven’t read it yet). But that really is just the tip of the iceberg. So, today, I thought I would write a little more in-depth about what I do and how I do it…

First, let me introduce you to something I’ve spent a lot of time with over the years: ceramic photomicrographs. These are photographs taken of very small slices of ceramic (30 microns or 0.03mm thick to be precise) under a light polarising microscope.

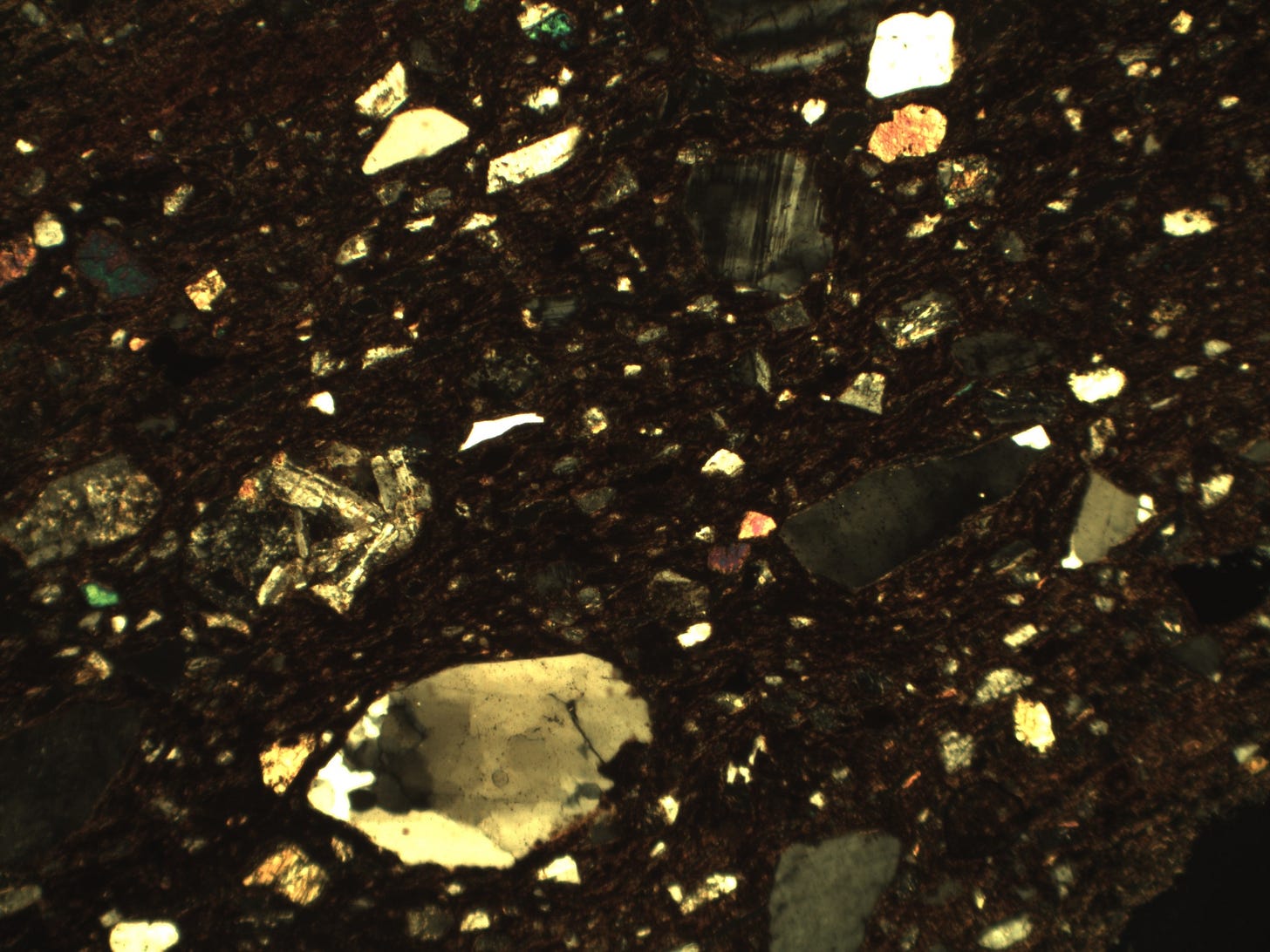

What can be seen in this image of a thin section is the make-up of a ceramic from an early 1st millennium CE site located on Bugala Island in Lake Victoria Nyanza, modern day Uganda. Under the microscope, ceramics can be found to have three main components: inclusions such as minerals and rock fragments, the very fine clay matrix, and voids. The relative percentage of these three components in the samples, as well as the size, shape, and frequency of the voids and inclusions enable you to characterise it, compare it to others, and ultimately, to interpret it.

From a preliminary look at a sample it is often possible to identify the rock type the clay derives from. The types of minerals and rock inclusions present, as well as their size and angularity/roundness, will be indicative of either a sedimentary, igneous or metamorphic origin. This is incredibly important information for the archaeologist because it can quickly be established — through studying geological maps — whether or not the ceramic could have been made from a local raw material. On the other hand, if the sample is metamorphic in origin and was found in a geologically igneous landscape, we can safely assume some sort of trade, exchange or movement of people occurred in the past.

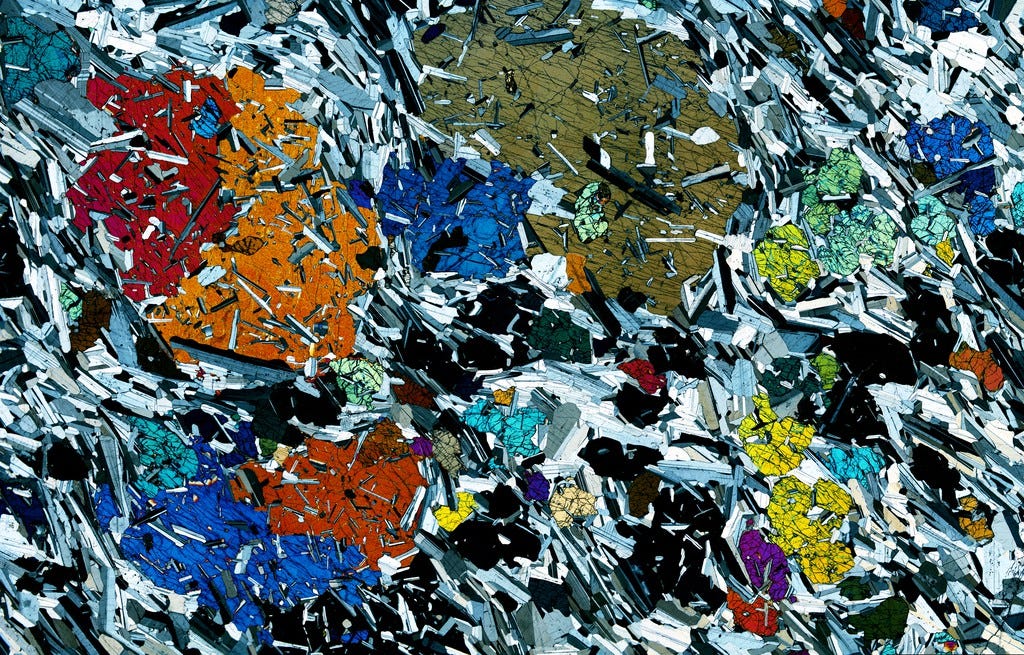

*Just as a side note, looking at minerals and rocks under the microscope is absolutely fascinating and they are incredibly beautiful. Take this Gabbro (below), a mafic intrusive igneous rock from the Isle of Rùm in Scotland: it looks like a piece of modern art! The striking, bright, colourful minerals you can see are clinopyroxene and olivine (one of my favourite minerals), while the black and white rectangular shards are plagioclase feldspar. Gabbro is formed by the slow cooling of magma extremely deep beneath the earth’s surface, and it’s this slowly cooling temperature and the different melting temperatures of the minerals that gives this rock such a unique appearance.

Before I digress too much, let’s get back to pottery. When looking under the microscope we are also searching for evidence of the manipulation of raw materials. For example, temper — such as shell, sand and crushed up old pottery (grog) — can be added to a clay paste to improve its workability. Grog, is another topic i’m a bit obsessed about, but I’ll leave that for another post…

Once we have a collection of thin sections from an archaeological site or a region, the next step in the analysis is to group them. By establishing which are similar and which are different based upon their composition it is possible to obtain an overview of ceramic production.

If, for example there are two very prominent groups, one made from a calcareous sedimentary clay with shell temper, and another from a residual (primary) igneous clay, we might suggest that there were two distinct ways of making and preparing pottery in the region. This could be traditions indicative of two different social groups, villages or workshops. It is also possible that one type (fabric group) was used for more specialised ceramics made by elite craftspeople on a large scale, and the other was used by individuals in small household based productions who produced ceramics part-time or seasonally.

Of course, getting to the point where you can start to make these interpretations involves a lot more than just looking at thin sections. Our conclusions need to be based on the findings combined with extensive archaeological evidence such as the context in which the ceramics were found, their forms and uses, the origin (provenance) of the clay raw materials and any other relevant information.

It is a bit of detective work to try and piece all the evidence together and to present the best explanation based on that evidence. A great example of this is a study undertaken on possibly some of the most famous ceramic objects ever made: the terracotta army of Qin Shihuang.

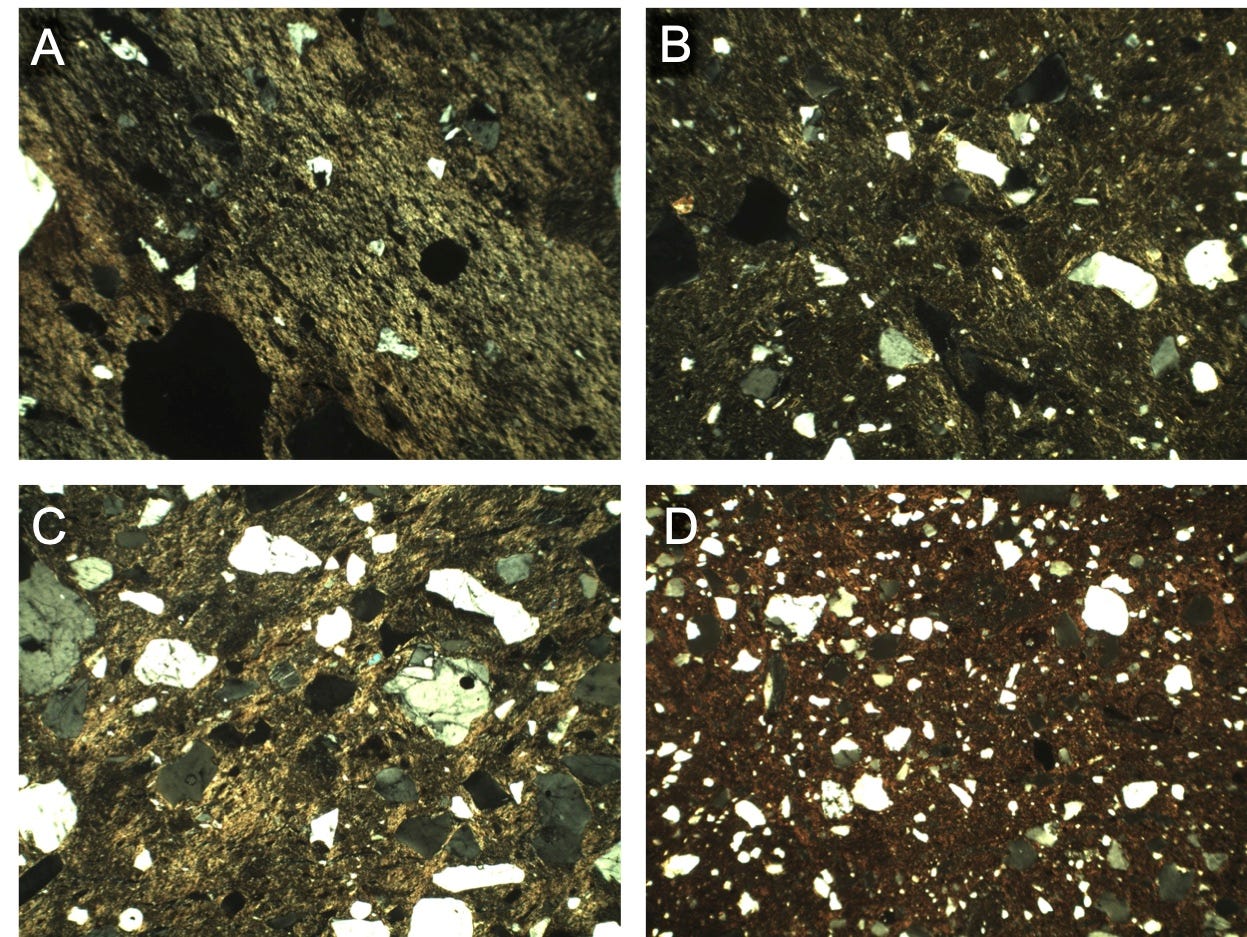

There is no doubt that scale of the production for the army was immense. To date 7,000 terracotta figures have been uncovered in three pits, but as the site has not been fully excavated, it is thought that there may be many more. The organisation of the production must have been expertly managed, but until recently we had no idea where the workshop/s making the terracotta figures were situated and where the clay originated. What we did know, was that the production was highly structured, for example, standardised moulds were used to create certain body parts. What is incredible however, is that each of the faces are unique, as if they were based on real living people.

Thin section analysis of fragments of the warriors in the largest of the pits (Pit 1) revealed that a consistent clay paste had been used in production, with the clay deriving from a source close to the site1 . The main interpretation posed by the authors (including my PhD supervisor at UCL), is that the initial collection and manipulation of the raw materials into a workable clay paste was done first by a separate workforce before it was taken and distributed to the various workshops responsible for building the figures. This ensured that all of the workshops (it is assumed there were more than one due to the scale of the production) were using the same clay that would then create the same finish and appearance once fired.

These findings indicate just how controlled all the levels of the production were and provides further insight into just how much time, effort and skill went into the preparation of the First Emperor of China’s Mausoleum.

I think I will leave it there for now, but this site and the ceramic objects (not only warriors!) found there are definitely going to be the topic of another post.

Source: Quinn, P.S.Q, S Zhang, Y. Xia & X. Li. 2017. Building the Terracotta Army: ceramic craft technology and organisation of production at Qin Shihuang’s mausoleum complex, Antiquity 91 (358), pp. 977

Wow, the photomicrographs are incredible, they look like works of art themselves! thanks for sharing, I need to learn more about this now!!