First, an apology.

Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to write my weekly Substack for the past few weeks. I came down with a nasty case of Norovirus, and sitting at my computer and writing was the last thing I wanted to do. Then, last week, I was completely swamped, catching up on work. However, I’m now back to normal and excited to share some of the findings from my newly published research.

While researching the manufacture of Egyptian clay figurines at the University of Pisa (see my previous post "Figurines" for more details), I noticed that the anthropomorphic (human) figures often included marks and paint suggesting body decoration—possibly tattoos, scarification, body paint, or jewellery. This piqued my interest, and I reached out to my friend and colleague, Dr Cristina Alù1 an Egyptologist, to collaborate on further research.

[Just a quick trigger warning that there are some photos of human mummified remains later in this post]

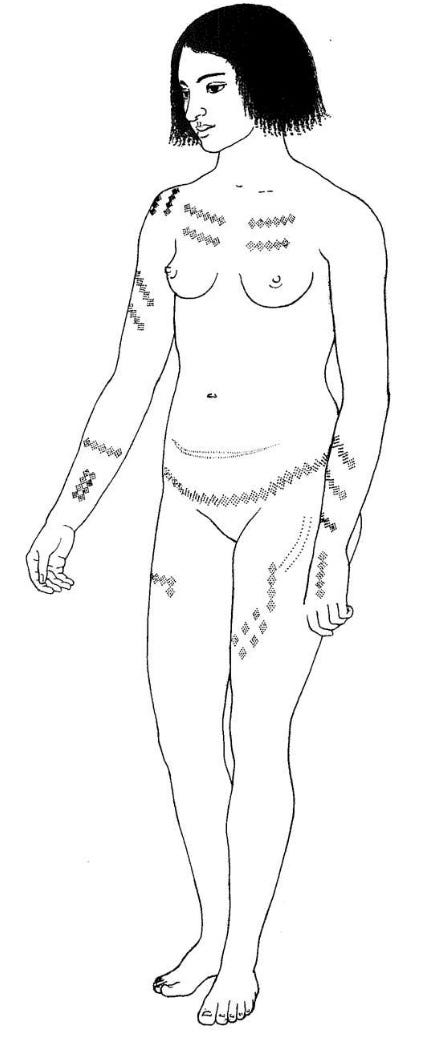

The picture above shows some of the figurines I was studying and the common marks and decoration that are added. As you can see, small dots, which we refer to as punctates, are often applied using a pointed tool. These are typically found on or around the navel, waist, neck, chest, and down the sides of the figurines. Additionally, horizontal and zigzag lines are incised in various places on the chest, stomach, and sides of the torso, with red or black paint sometimes applied around the arms, navel, or over the zigzag lines.

But how do we determine what these marks represent? How can we be sure they aren’t just random decoration? In our research, we examined two main types of evidence:

We searched for similar decorations on other objects from the same period.

We looked at actual tattoos and scarification found on ancient Egyptian mummies.

Other Artefacts

So, what evidence did we find from other objects? We looked at items made of faience (an Egyptian glass material), wood (artefacts known as paddle dolls), and actual jewellery. One of our main conclusions was that the lines of dots seen around the hips of many figurines likely represent a piece of body ornamentation known as a girdle.

The faience figurine above depicts a woman wearing a cowrie-seed girdle, similar to the one shown in the image below. While this detail is quite refined, it would have been much harder to achieve on the clay figurines we studied. It’s likely that simple dots impressed around the hips were the most effective way of representing these girdles on the clay figurines. You can also see dots arranged in an ‘X’ across the chest of the faience figure, which we believe represent a beaded necklace worn across the body. Although we haven’t found exact matches for this on our figurines, there are examples of punctates applied around the neck and chest that suggest necklaces.

Human Remains (mummies!)

What is absolutely mind-blowing, is that we have direct evidence of actual tattoos on mummies from 3,000-4,000 years ago. Below is a picture of one of the most remarkable examples— a neck tattoo found on a mummy from the site of Deir el-Medina, a workman’s village near Luxor, Egypt, where the Valley of the Kings was constructed. And this was not the only tattoo… she had at least 30 all over her body including on her arms, legs and back2.

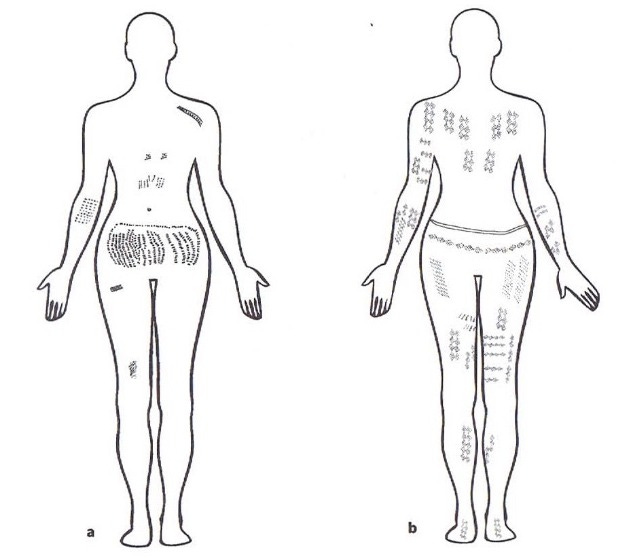

However, this mummy is a little too late for the time period we were researching. Much more contemporaneous examples are mummies from Deir el-Bahari3 and Hierakonpolis. The tattoos and scarification marks on their skin include lines above the hips, lozenge patterns, and rows of dots on the arms, stomach, chest, and around the pubic area (I can only imagine how painful that must have been!). Many of these markings resemble those found on the clay figurines.

Interestingly, one particular mummy (from Deir el-Bahari, pit 23) showed a string of lozenge tattoos above the hips, in the same place we would expect to see a girdle:

“It is therefore possible that lines of punctates or incisions on the hips or lower stomach could also be indicative of modifications (tattooing or scarification) applied to the skin itself. We suggest that girdles and girdle tattoos may have been interchangeable in reality with the motif, and bearing a symbolic function. Thus, the symbolism of the girdle was the most important element, both on the human female body and on their representations in clay”

(Alù and Page 2024:184)

Another interesting example of ancient Egyptian tattoos comes from the mummy of Amunet, a priestess of Hathor, also excavated at Deir el-Bahari. Although her tattoos have been documented in older publications, their accuracy is uncertain due to revisions and changes over the years. BUT a really exciting project is underway to re-examine and document the mummy — and most importantly her tattoos(!) — so hopefully, I will be able to update you on their results in the coming years4.

Our Main Conclusions

The key insight from our research is that these marks seem to convey far more than mere decorative elements. They likely represent body ornamentation, tattoos, and other forms of cultural expression. What makes these figurines particularly significant is that they were created by ordinary people, offering us a unique window into their lives and beliefs. The details they chose to incorporate are fundamental to understanding what they valued and what featured in their daily existence. Could this indicate that tattoos were commonplace among everyday individuals, not just the elite few whose mummified remains have endured through millennia? Or were these figurines perhaps depicting a specific class of individuals—such as priestesses—who adorned themselves with certain types of jewellery and tattoos? If so, might this suggest that the figurines held a specific ritualistic or symbolic purpose?

These are all questions that the current research project I am part of is trying to understand. And I will keep you updated with all the new research and publications when they come out.

Our paper was published in the book Clay Figurines in Context: Crucibles of Egyptian, Nubian, and Levantine Societies in the Middle Bronze Age (2100–1550 BC) and Beyond, if you’d like to read more. Also, feel free to check out all the fascinating research referenced in the text and footnotes.

References mentioned in the text and images:

Alù, C., H.B. Page, 2024. Decoding Decoration on Middle Kingdom Egyptian Clay Figurines: Body Modification or Ornamentation?, in G. Miniaci, C. Alù, C. Saler, V. Forte (eds), Clay Figurines in Context: Crucibles of Egyptian, Nubian, and Levantine Societies in the Middle Bronze Age (2100– 1550 BC) and Beyond (London: MKS 17), pp. 171-87.

Austin A., & C. Gobeil, 2017. Embodying the divine. A tattooed female mummy from Deir el-Medina, BIFAO 116, pp. 23-46

Friedman, R., 2017. New Tattoos from Ancient Egypt, in: L. Krutak. & A. Deter-Wolf (eds), Ancient Ink: The Archaeology of Tattooing (Washington), pp. 11-36.

Roehrig, C., 2015, Two Tattooed Women from Thebes, BES 19, pp. 527-36.

Egyptologist, currently a postdoctoral research fellow at the Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale in Cairo.

For more information: A. Austin and C. Gobeil, 2017. Embodying the divine. A tattooed female mummy from Deir el-Medina, BIFAO 116, pp. 23-46 http://www.ifao.egnet.net/bifao/116/03/\

Image of mummy from Pit 23, Deir el-Bahari is from: Roehrig, C., 2015, Two Tattooed Women from Thebes, BES 19, pp. 527-36.

What an amazing job you have! Such a good read, so beautifully written - my favourite newsletter yet!